Carrolling in Poland?

Lewis Carroll Societies exist all over the world, but what about Poland? Sadly, the answer is no. Although on his fabled 1867 trip to Russia, the Rev. Dodgson himself visited Danzig (Gdańsk) and Breslau (Wrocław) – then part of Prussia – Carroll is not at all popular there today. Children associate Alice in Wonderland with movies rather than the book. However, the Alice books are quite popular among scientists at universities; iIt seems that almost every college has one professor studies them.

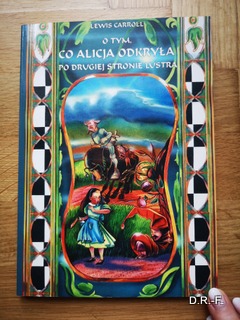

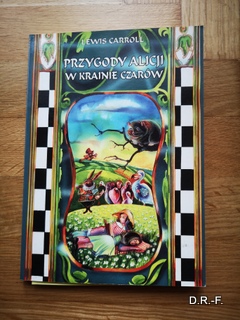

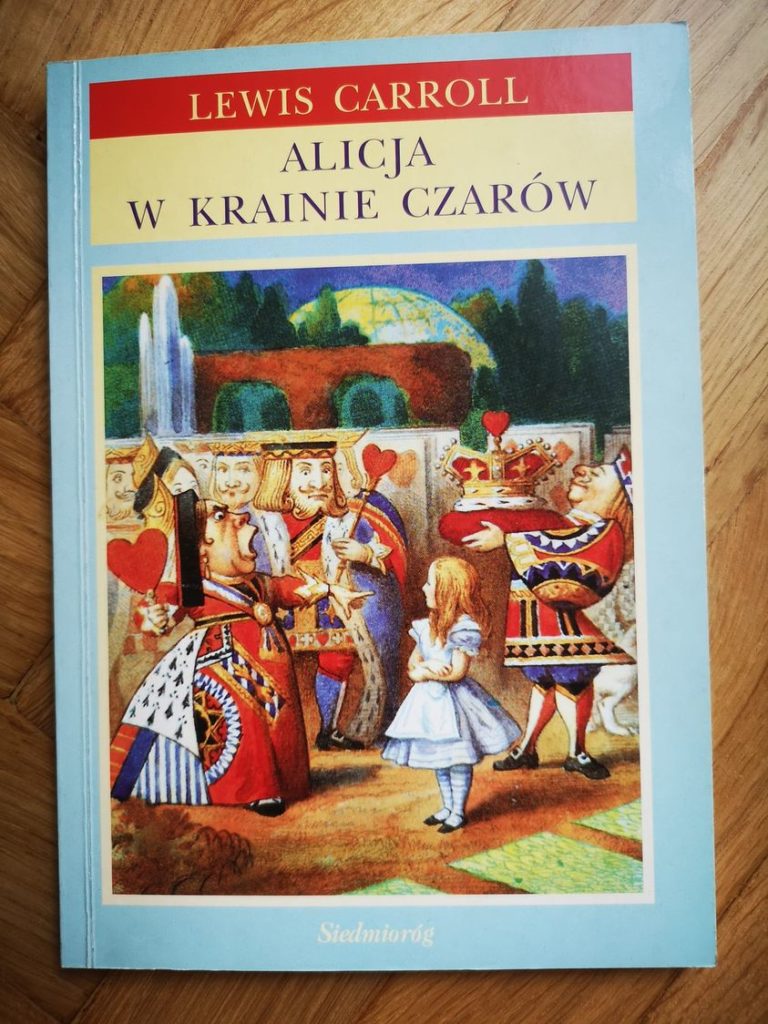

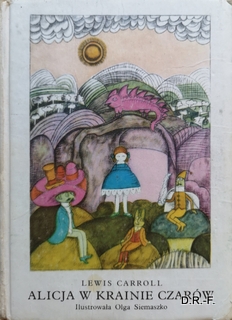

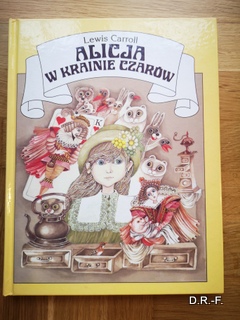

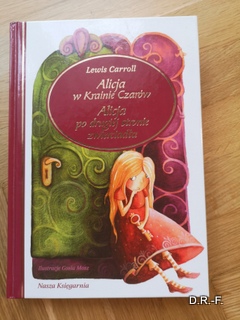

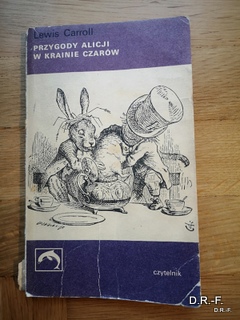

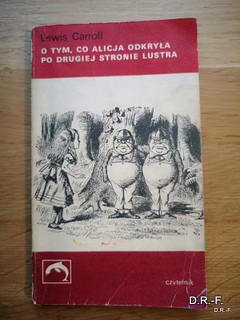

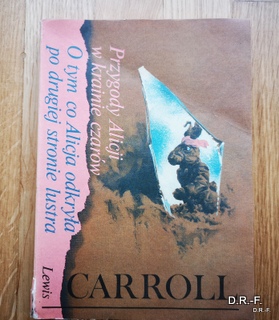

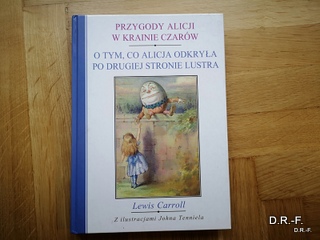

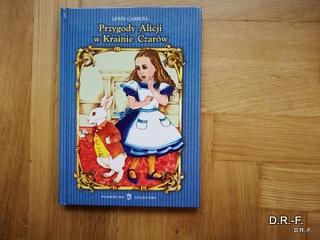

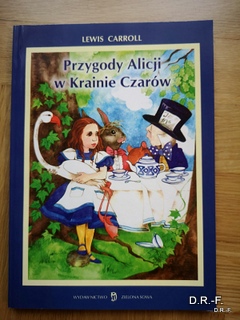

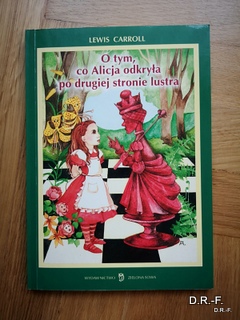

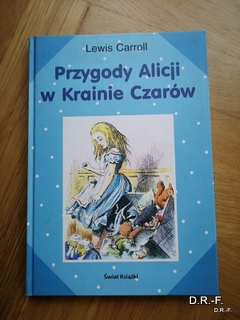

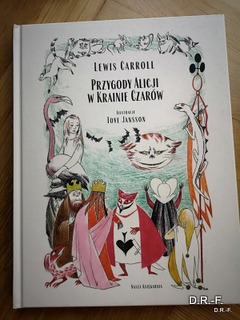

Various editions of Alice have appeared over the years in Polish bookstores. Most of them are aimed at younger children, and they are usually very colorful. Carroll’s text is much abbreviated, and Magdalena Machay, one of its translators, specially prepared Alice for school reading. (In my opinion, this is not a good idea. If children have to read Alice and answer test questions, the book will lose all its charm.) Although it is commonly perceived, as a book for children, some adult readers find Alice’s content interesting; the sixteenth (!) Polish translation, in an edition illustrated by Salvador Dalí, was published last year and quickly sold out.

In January, I gave a talk on Alice and showed a small part of my collection at our local library. Not a single audience member had read Alice! Everyone was surprised by the history of the book’s creation, its popularity around the world, and its impact on culture and mass media.

The answer to the mystery of Alice’s unpopularity in Poland can be traced to our country’s history. During the Victorian era, Britain was the most powerful empire, and Poland had disappeared from the map of Europe. Our country was divided between three neighboring countries for over 120 years. While Alice happily spent her childhood on picnics or learning English poems in class, her Polish friends had to speak German or Russian; Polish language was banned in schools. As in Alice’s Adventures, Polish children fell down a rabbit hole into a foreign culture and were generally met with hostility. If they used the Polish language in public, they faced severe punishment, even flogging.

The living conditions for adults in both countries were also completely different. Poles were constantly fighting for independence. In 1863, as a result of the January Uprising, which ultimately failed, many men were killed or sent to Siberia. Many Polish families lost their property, families became poorer, and lost their fathers because they had been sent to prison — a far cry from the privileged life of an upper-class British girl, who would be hard for them to relate to

The occupying forces also controlled literature; writers and poets were not allowed to use patriotic phrases. A good example is a poem by Maria Konopnicka. For Carrollian, the word “river” evokes pleasant associations with the Golden Afternoon. In Konopnicka’s poem, the river is a symbol of their homeland; the ice covering the water symbolizes enemy countries. Even though the river seemed trapped by ice, water still flowed beneath it. Spring is hope – the ice had to melt finally.

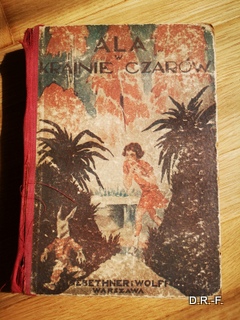

Maria Konopnicka also penned the popular fairy tale O krasnoludkach i sierotce Marysi (Little Orphan Maria and the Dwarfs ) published in 1896. Fourteen years later, Polish children could read Alice in Wonderland translated into Polish by “Adela S.” Both books describe the adventures of little girls who meet fairy-tale characters, combined authenticity with fantasy. However, Mary’s situation is more akin to Mabel’s than Alice’s.

I must be Mabel after all, and I shall have to go and live in that poky little house, and have next to no toys to play with, and ah! Ever so many lessons to learn!

For over a hundred years, the Church was usually the only place where Polish could be spoken. Consequently, religious associations brought together patriotic people. To some extent, the church became a symbol of the country. When Poland gained independence in 1918, the most important thing was to unite Poles who had been part of three different, hostile countries for 123 years. The reborn state had to unify the education system, and nationalistic education became a priority. Alice’s world, full of nonsense, seemed less necessary than local patriotic stories.

Polish children could read the fairy tale Little Orphan Maria and, as teenagers a few years later a 1911 Anne of Green Gables and W pustyni i w puszczy (In Desert and Wilderness (1911) by Henryk Sienkiewicz, later a Nobel Prize winner for Quo Vadis.). Both books became extremely popular among children and adults, perhaps because the readers could identify with the main characters. Unlike Alice’s, the action of both books was in line with the conditions in which young readers lived in Poland, even if the action in W pustyni takes place in Africa.

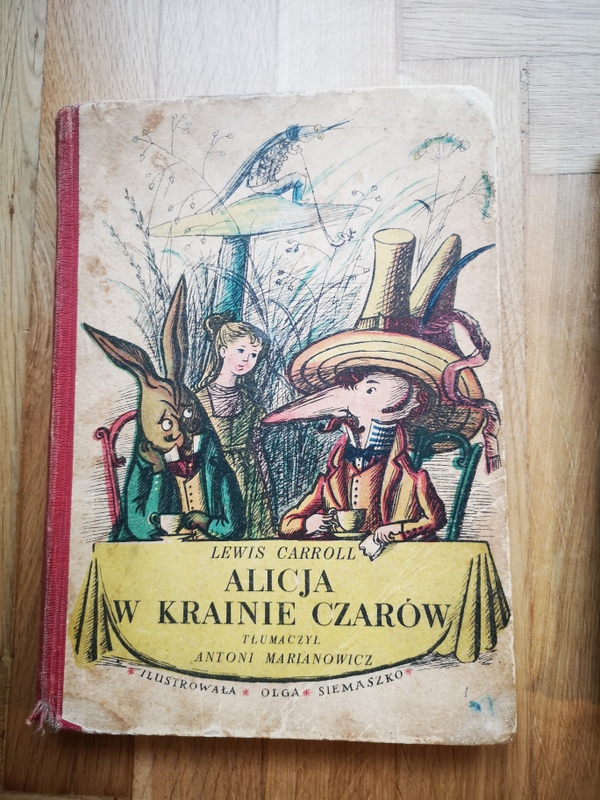

After WWII, literature, even for children, was conditioned by politics. Some writers and books were placed on the banned list. Literary scholars attribute the appearance of the third translation of Alice, by Antoni Marinowicz in 1955, to chance or oversight. The next generation of readers had to wait almost twenty years for a new translation, which included Through the Looking Glass.

In 1990, Robert Stiller, the fifth translator, wrote a much longer foreword to his bilingual Alice, relying on The Annotated Alice so readers could learn more about the Anglican pastor and his work. It was illustrated by Dušan Kállay, and I have often heard contemporary adults say that they were more afraid of the illustrations than the text.

For all these years, the author of Alice has been an obscure figure in Poland. This fact, Poland’s long struggle for survival, and its focus on patriotic literature are in my opinion the main factors in the absence of a Lewis Carroll Society in Poland. But with all these translations out there (not to mention two of The Snark), the relative stability of Poland in recent years, and globalization due to the Internet, one has hopes for a “Towarzystwo Lewisa Carrolla w Polsce” in the future.

____

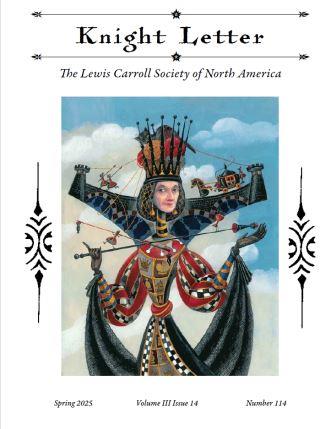

® Originally published in the Knight Letter, the magazine of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America, Volume III, Issue 14, Number 114, Spring 2025

![5.3.[25]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.3.25.jpg)

![7.1.[26]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/7.1.27.jpg)

![8.1.1.[27]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.1.1.28.jpg)

![8.1.2.[28]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.1.2.29.jpg)

![8.2.2.[30]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.2.2.31.jpg)

![Paszporty Alicji 8.2.1.[29]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.2.1.30.jpg)

![5.1.[23]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.1.23.jpg)

![5.2.[24]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.2.24.jpg)