Franciszka Themerson Illustrator Spotlight

Franciszka Themerson was born in Warsaw in 1907. Jakub Weinles, her father, was a well-known painter who created art around Jewish culture. Her mother, Łucja Kaufman, was a pianist, and her older sister, Maryla Weinles –Chykin became an illustrator and a pianist as well.

As family legend says, Franciszka was born with a pencil in her hand. She made her first drawing before she could walk,. The family home had a huge influence on a talented child; she grew up in a house full of pictures, paints and brushes.

As family legend says, Franciszka was born with a pencil in her hand. She made her first drawing before she could walk,. The family home had a huge influence on a talented child; she grew up in a house full of pictures, paints and brushes.

When Franciszka was only five, she experienced a memorable artistic crisis, possible one of the factors that later influenced her painting technique. She was sitting in front of the large mirror and was trying to draw the reflection in her sketchbook. Her eyes turned out to be an insurmountable obstacle. As she recalled years later:

“I couldn’t make my penciled eyes look at me with the same intensity as my eyes in the mirror. So I tried to strengthen them. I made them blacker and blacker. And they became less and less like my own eyes, which were light blue. But I had no means yet to translate the intensity of a look into a drawing, or even to understand that this was what I wanted to do. So I pressed my pencil harder and harder until two holes appeared in the paper and, exhausted, I burst into tears. Our old cook, hearing my howling, ran from the kitchen, took me in her arms, and, seeing the damage I had done, tried to console me, saying: “Don’t cry, sweetheart, I’ll buy you another sketchbook.” She did not see the work of art. She only saw two holes in the paper. Upon which I cried still more bitterly. This was my first experience of not being understood by the public.”[1*]

Franciszka’s father, had a painting studio where he gave lessons to a dozen or so students of various ages, including eight-year-old Franciszka. Many years later, she remembered how she felt anxious and excited sitting in front of an easel with a huge sheet of white paper pinned to it. As an academic painter, Jakub Weinles taught his students how to make a rapid sketch of the model’s head. Students had to follow a precise procedure. Only after measuring the proportion of the nose and mouth and marking the exact place for the eyes were they allowed to sketch the details – but only of the right eye. When little Franciszka was leaving the studio, twelve beautifully modeled eyes were staring at her from the easels.

“Never has any surrealistic picture made such a strong impression on me as those tweleve living, single eyes which inhabited my father’s studio. However, the magic vanished when all twelve pictures were finished the following day”.

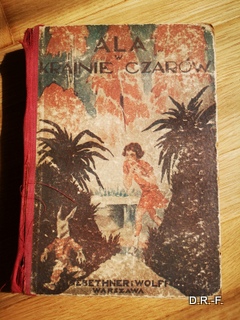

Franciszka’s life was as unusual as Alice’s stories. She first studied at the Academy of Music and then at the Academy of Fine Arts in Warsaw. She graduated in 1931 and the same year married Stephan Themerson, a writer and experimental photographer. During the 1930s, the Themersons became leaders in a small but vital Polish film-making avant-garde, financed in part by a series of inventive books for children. The Themersons made five short experimental together, most of which are lost now. Stefan wrote varoius articles for school tex books. He also wrote at least ten children’s books that Franciszka illustrated; Narodziny liter [The Birth of Letters] is still in print in Poland.

In 1938, the Themersons left Warsaw for Paris in search of a wider artistic environment. Franciszka was illustrating children’s books, while Stefan edited a children’s newspaper supplement and wrote poems. A year later, World War II broke out, and the Themersons volunteered for war service. Stefan joined the army in France, while Franciszka managed to get to England and became a cartographer for the Polish Government-in-Exile. The couple had almost no contact. They wrote letters to each other but could not mail them, since they had no way of knowing where their spouse was at any given time. They each put their letters in a drawer, and they were later published as. Unposted Letters (Gaberbocchus & De Harmonie, 2015). In them, Franciszka drew pictures of the devastation she saw during the bombings of London.

In 1938, the Themersons left Warsaw for Paris in search of a wider artistic environment. Franciszka was illustrating children’s books, while Stefan edited a children’s newspaper supplement and wrote poems. A year later, World War II broke out, and the Themersons volunteered for war service. Stefan joined the army in France, while Franciszka managed to get to England and became a cartographer for the Polish Government-in-Exile. The couple had almost no contact. They wrote letters to each other but could not mail them, since they had no way of knowing where their spouse was at any given time. They each put their letters in a drawer, and they were later published as. Unposted Letters (Gaberbocchus & De Harmonie, 2015). In them, Franciszka drew pictures of the devastation she saw during the bombings of London.

After two years of separation, the couple was reunited in London in 1942 when Stefan was sent to join the film unit of the Polish Ministry of Information and Documentation in London. In 1943, he and Franciszka made a short film, Calling Mr Smith, to make UK citizens aware of the atrocities committed by the Nazis in Poland and to stop Hitler’s plan to rule the world.

In 1948, Franciszka and Stefan founded their highly original publishing company, Gaberbocchus Press, of which she was the art director. The name “Gaberbocchus” was borrowed from a Latinization of “Jabberwocky” by Carroll’s uncle Hassard H. Dodgson. The logo was a drawing of an amicable dragon, often found reclining and enjoying a book; Franciszka re-invented the dragon many times over the years. The couple printed the first two books on a manual press in their flat. Unlike other small émigré publishers of that time, the Themersons’ ambition was to introduce British readers to the works of contemporary European writers – Alfred Jarry’s Ubu Roi among them. For over thirty years of the publishing house’s existence, the unique look and feel of Gaberbocchus books was largely due to the Themersons’ involvement in the design and production. Gaberbocchus titles show thought, deliberation and planning. Stefan Themerson described their approach: “When we design a book, what we aim at is a best-looker not a best-seller.” Additionally, the Press allowed them to publish their own experimental work in whatever form they chose.

In 1954, they became British citizens. They also founded an art salon called Gaberbocchus Common Room where, on November 28, 1957, Franciszka gave a talk titled “Twelve Living Eyes In My Father’s Studio.” She talked about her pictorial language: She didn’t think it out; she painted it out. Some people called her an ‘intellectual’ painter, while others asked her what her pictures were all about. According to Franciszka, painting can be the painter’s way of thinking. She once said that “the laws of gravitation have no right in the space of a picture which has its own laws.”

During her life, Franciszka painted, drew, illustrated, designed books and magazines, created theatrical scenery, and lectured at art academies. She had solo exhibitions throughout England and Europe. Her style of figurative painting evolved; she called it “bi-abstract”; one critic described it as “modern cave painting.”

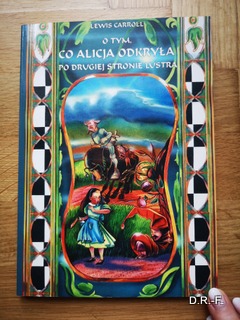

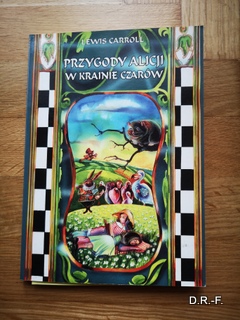

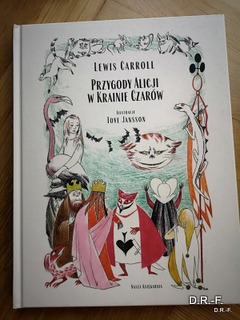

During the war, the publisher Georg G. Harrap commissioned her to illustrate Looking-Glass; she finished her drawings in 1946. But then he decided against publishing the book because “the market situation was difficult.” It had to wait until 2001, when her niece, Jasia Reichardt, arranged for its publication (in English) by Inky Parrot Press (KL 68:13, 89:5).

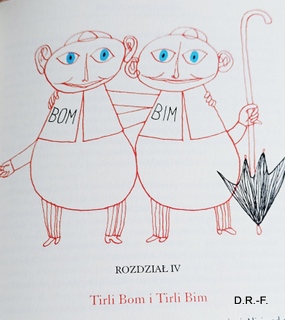

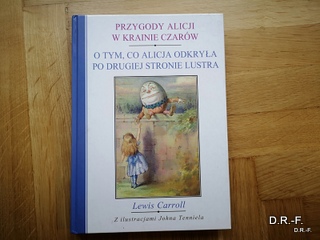

The images in Franciszka’s illustrations represent two worlds. Only the three-dimensional Alice, drawn with a black line, resembles Tenniel’s drawings and the real world. The two-dimensional imaginary characters in the Looking-Glass world are flat and colorful. The Red Queen and her entourage are red, while the White Queen and her companions are blue. Small, curious, kind, and sometimes a bit stubborn, Alice is the stimulator of the developing novel: her gaze brings other characters to life.

Franciszka and Stefan Themerson both died in 1988. Jasia Reichardt has catalogued their archive and looks after their legacy. In 2015 the entire archive was deposited in the National Library in Warsaw, Poland; the three- volume catalogue was published in 2020 MIT Press in 2020. A book-length biography called simply Franciszka Themerson was written by Nick Wadley and published by The Themerson Estate in 2020.

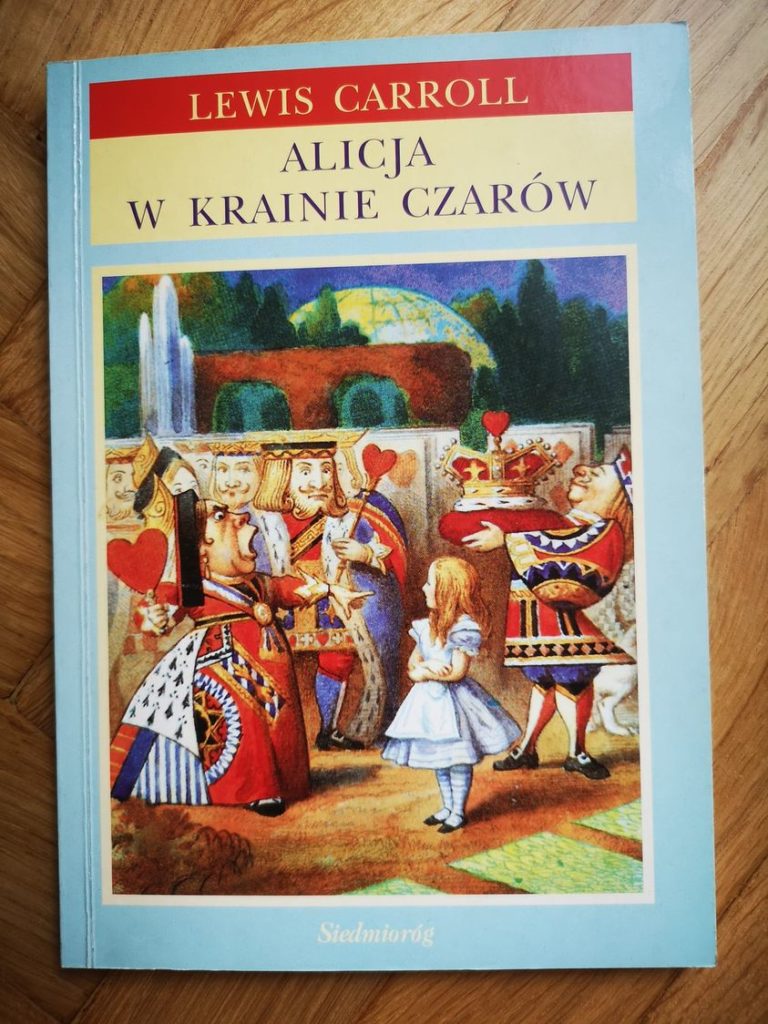

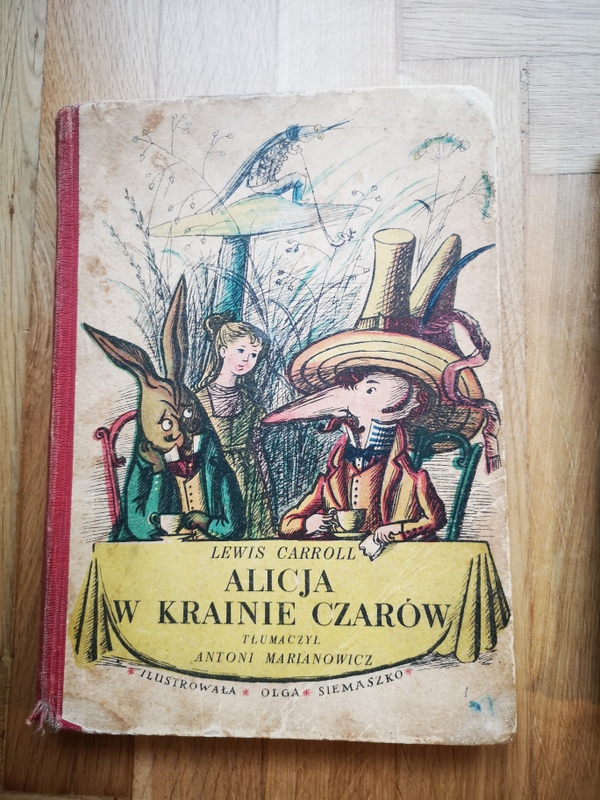

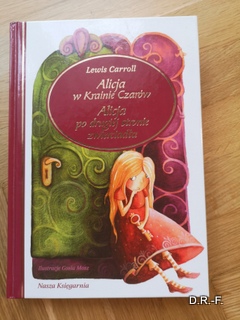

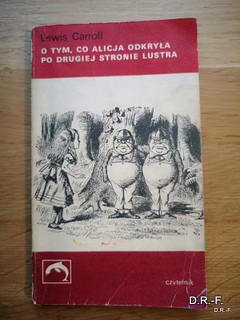

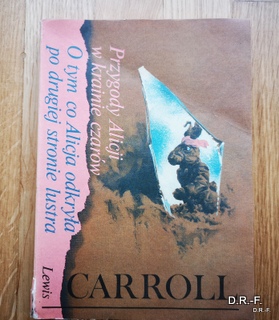

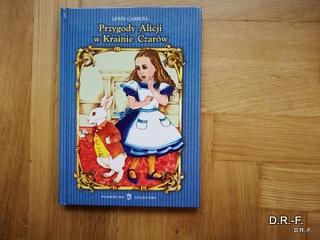

The fine-press Inky Parrot edition is pricey and difficult to find. Fortunately, Franciszka’s lovely illustrations are also readily available in trade editions: in Spanish as A través del espejo: y lo que Alicia encontró allí (Media Vaca, 2013), in Polish as Alicja po drugiej stronie lustra (Fundacja Festina Lente, 2015), and in French as Alice à travers le miroir (MeMo, 2022), but has yet to find an English-language trade publisher.

Endnotes

From Płock and for Płock. Gallery of the Płock inhabitants of the 20th century. Themerson Gallery

O Franciszce pisałam wcześniej tutaj: https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/franciszka-themerson-i-jej-alicja/

——

Originally published in the Knight Letter, the magazine of the Lewis Carroll Society of North America, Volume III, Issue 12, Number 112, Spring 2024″

![5.3.[25]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.3.25.jpg)

![7.1.[26]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/7.1.27.jpg)

![8.1.1.[27]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.1.1.28.jpg)

![8.1.2.[28]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.1.2.29.jpg)

![8.2.2.[30]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.2.2.31.jpg)

![Paszporty Alicji 8.2.1.[29]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/8.2.1.30.jpg)

![5.1.[23]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.1.23.jpg)

![5.2.[24]](https://lawendowykapelusz.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/5.2.24.jpg)